Passwords. You're Doing It Wrong

· 11 min. read

I seem to be having difficulties getting into the mood to revise for an exam tomorrow. It is what I should be doing, but what I really want to be doing is to code all day. Unfortunately, as it is exam season I have decided to self-impose a ban on coding until I have completed all my exams. Fortunately, I do not recall banning myself from making a blog post so here we go.

If you are running a website that requires a user-password-based authentication system there is a high chance you are probably handling the password poorly (at least in my books). Indeed, several e-commerce and e-banking websites are doing it wrong too. As a disclaimer, I am neither an expert in web security nor am I one in user experience. The following post is not targeted towards a layperson. I am merely synthesising a list of bad questionable password practices by web developers and they are based on personal observations (albeit, with some support from the web community).

Unnecessary requirements...

Maximum password length.

I can only identify six key reasons why any website would choose to set an upper bound limit on a user's password:

- The use of legacy systems and/or a legacy password hashing function;

- Convention and/or a guideline set by a very naïve, higher authority;

- To store the password in plaintext or encrypted plaintext (different from hashing) [to accommodate a database schema];

- Developing from point 3: to prevent injection-based attacks;

- Reduce likelihood of users forgetting?

- To mitigate (D)DoS attacks.

I do not find reasons one to four reasonable at all. They are not valid excuses in this day and age.

Your authentication system should be "designed for failure". With the increasing number of prominent database breaches, it is no longer logical (rather, it never was) to assume your users' confidential data are not susceptible to compromise. As such, it is not logical to store passwords in plaintext or in an encrypted format that is either reversible or generated by a weak cryptographic hash function. You are exposing your users (particularly those who share their password across different websites) to risk in the event your users' credentials are exposed to malicious individuals.

Reason 4 should not be an issue once you have password hashing in place as you are merely storing the hashed password, and thus, you should neither be passing any system-sensitive command to the database nor should you be validating the original password in plaintext. The length of a user-entered password will not affect the length of the hashed password, and hence, it will not affect the database schema (it will remain consistent).

Reason 5 should be accounted for via automated password recovery processes. Users should be given the freedom to set a password of any length (even if they are more likely to forget them, but that is not for you to judge) inasmuch as it is not detrimental to your website (reason 6). In my opinion, it is bad UX to set such hard limit.

Reason 6 is a machine problem, not a user one, and they should not be punished for it. The machine should be configured to deal with DoS attacks and to drop adverse request handlers (e.g. via request thresholds, filters etc). DDoS attacks may be mitigated by building the website to deal with CSRF (e.g. via captchas, hidden key, etc). Admittedly, dealing with DDoS attacks are far more complex, but by preventing remote requests you are removing one source of attack and you will increase the complexity for the attacker. Worst-case scenario, it is justifiable to set a generous upper bound limit.

We set a lower bound (minimum) limit for passwords because shorter passwords are easier to guess and/or brute force (for humans and machines alike). Thus, it is only logical to allow for longer passwords with higher entropy.

Passwords with special characters.

Websites that do not allow special characters in passwords seem to imply the same reasons postulated above. Indeed, this practice strongly implies to me that the web developer is concerned with the content of the password as it may be malicious (reason 4), and this makes me very concerned as well.

As I have explained already, if the password is hashed this should not be a concern at all. You are not passing system-sensitive commands. You are passing gibberish. If it is a concern, then chances are it is probably stored in plaintext or in a format that is reversible (and potentially harmful for the system in the web developer's perspective). This should raise some serious red flags.

Instead, special characters should be encouraged. They add complexity to the resulting hashed password thereby increasing the time it will take to crack the password via hardware and technique-based attacks (e.g. dictionary, brute force, etc). On the contrary to XKCD-936, it is no longer secure to set a purely alphanumeric password, let alone one that is composed of words. Granted, it does increase the entropy of your password and reduces the likelihood of someone guessing it. The concern arises however, from the assumption [that I have previously made] that if the hash of your users' password are stolen, they are vulnerable to being cracked by dictionary-based attacks.

Freedom and predictability.

Imposing machine requirements on passwords is fundamentally bad UX and bad security design.

Users should be given as many opportunities as possible to safeguard their own accounts and identities. Web developers should accommodate for this, and not the other way around. A restriction-less password is the first step in doing so. It will grant users the freedom [and arguably, the responsibility] to ensure the security of their own account. Users with a greater affinity towards higher quality passwords should not be restrained by petty limits on the length and/or characters. Other [strongly encouraged] steps may be taken including password expiration, two-factor authentication, limits on failed authentication attempts (lockout), IP address restrictions, SSL etc.

It is also a bad security design as it helps attackers by reducing the range of possible passwords. For example, an attacker needs to only test for alphanumeric passwords if a website is set to allow alphanumeric passwords only. There is no need to account for other characters. Thus, a lack of password definition / rules will provide another variable for the attacker to account for thereby increasing the complexity (or rather, broadening the assumptions).

A note on hashes.

Cryptographic hash functions generally return a fixed-length hash value. Consequently, there is a chance that a hash of one string may be the hash of another string. This phenomenon is known as a hash collision, and while the possibility exists, some cryptographic hash function are more resistant to it than others (the cost of discovering these collisions, e.g. via birthday attacks, are much higher). Consequently, there may be some diminishing returns beyond some password length depending on the strength of the cryptographic hash function used.

Password strength checkers and minimum score.

Password strength checkers rely on a custom security criteria which more often than not, is flawed. They are commonly calculated by measuring the entropy of the password or by comparing it to a set of regular expressions. High scores may be achieved by lengthier passwords (such as those composed purely of random words), but the overall quality of the passwords may not necessarily be high, for reasons explained above (they may even fall in a list of common passwords or patterns).

For someone who is not familiar to the concept of passwords such a mechanism would be useful for guiding the user towards a more complex password with greater entropy, and hence, theoretically greater security. Enforcing a score-based restriction is nevertheless bad UX (it forces users to behave like machines which may also give a false sense of security), and in some cases, it may be a bad security design if it forces users to conform to a certain pattern of password (e.g. start with capitals, include X or Y, etc).

Indeed, the findings in a research into the NIST model of password entropy (a heavily recommended scheme for estimating the entropy of human-selected passwords) showed that:

...the NIST model of password entropy does not match up with real world password usage or password cracking attacks. If that wasn't controversial enough, we then made the even more substantial claim that the current use of Shannon Entropy to model the security provided by human generated passwords at best provides no actionable information to the defender. At worse, it leads to a defender having an overly optimistic view of the security provided by their password creation policies while at the same time resulting in overly burdensome requirements for the end users.

Password Account recovery.

Assuming most "forgotten password" functionality relies on a user's e-mail address, then no credentials (the password in particular) should be sent to the user via e-mail, regardless of whether it is the user's original password or if it is a randomly generated password.

Indeed, for security reasons, under no circumstances should you have access to the user's original password. As I have previously mentioned, passwords should not be stored in plaintext or in a format that is easily reversible. It must be hashed using a reliable cryptographic hash function. Any website that sends you your password is clearly not handling your data securely, and it is probably not trustworthy.

It is also not advisable to reset the user's password. By setting a randomly generated password without the user's prior consent you are doing the following:

- Diminishing users' freedom and control over their data.

- Potentially jeopardizing users' security should they choose to write it down (due to its complexity) or should someone else see the password in their e-mail account.

- Developing from the previous points: it may increase the complexity (adds more steps) of the recovery process as the user is likely to change the automatically set password upon authentication.

The user should be given the freedom to set a new password immediately. This is probably how the user wants it to be anyway.

Measures should also be taken to secure the account recovery interface (e.g. via unique tokens, expiration, throttling, etc), but it is not for the purpose of this article to discuss. Refer to the definitive guide to form based website authentication for more information.

Password Data validation.

Users should be informed about the validation requirements before the validation process occurs, not after. It will save the user's time and it is less frustrating that way. They should not be expected to predict a system's design only to be punished for not being able to do so. Don Norman's "Error Messages Are Evil" summarises this problem succinctly:

A truly collaborative system would tell me the requirements before I did the work. If there are special ways you want stuff entered, tell me before I enter it, not afterwards. How many times must we endure the indignity of typing in a long string only to be told afterwards that it doesn't fit the machine’s whims (more accurately, doesn't fit the whims of the programmer)?

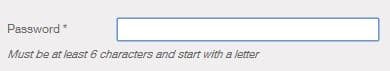

Restrictions may vary from one website to another. Thus, it should be made explicitly clear what would constitute an "acceptable password" (e.g. special characters, uppercase/lowercase, numbers, etc) if you do intend on setting restrictions. Take French Connection United Kingdom (FCUK) online registration form for example:

The developers only made clear the lower bound limits, but made no attempt at informing me of the specific upper bound limits (even after the form has been validated). Please do not force your users into a guessing game. It took me several attempts before I realised that the character limit was 12 and that I could not use special characters. By making the lower bound limits obvious instead of the upper bound limits, you are only encouraging users to go for the bare minimum (to avoid your otherwise annoyingly vague form rules and error messages).

Password masking.

Jakob Nielsen's "Stop Password Masking" thoroughly summarises the problems with password masking:

Usability suffers when users type in passwords and the only feedback they get is a row of bullets. Typically, masking passwords doesn't even increase security, but it does cost you business due to login failures.

...there's usually nobody looking over your shoulder when you log in to a website. It's just you, sitting all alone in your office, suffering reduced usability to protect against a non-issue.

It is a legacy design ingrained by browser vendors. We have adhered to it because it is simple and conventional. In reality, the lack of feedback makes us more prone to errors or bad password practices (e.g. simple passwords, copy-pasting, etc), and the former is exemplified by the need for an extra password field as confirmation (further complicating registration processes).

Nielsen instead recommends offering users a checkbox to have their password masked for high-risk locations (internet cafes) or high-risk applications (bank accounts). Indeed, Microsoft's Internet Explorer 10 have included a small icon for password fields that will allow users to view their password in plaintext.

If you have never heard of Nielsen, he is an acclaimed web usability consultant. He is known for publishing his usability heuristics in 1994. Currently, his heuristics are perhaps the most-used heuristics for user interface design. It is a set of guidelines that may be used to identify potential usability problems in a design (albeit, not strictly). You can run a heuristic evaluation on your own website through UX Check (a Chrome extension).

Do what we can with what we got.

Password-based authentication systems are inherently flawed, but they are the best we got with regards to ease of deployment, security, and usability (although projects like Mozilla's Persona are trying to challenge this). We should not make such a system worse than it already is. We should work towards perfecting it while striking a balance between security and usability.

Ultimately, code is law and the web developer is the legislator. As the legislator, you are responsible for the behaviour and the security of your users. You can make their web experience pleasant or unpleasant. You can do whatever you can to guarantee their security and the security of the information they provide you with, or you can just neglect them and deal with a PR sh*tstorm (for lack of a better word) when your complacency is exposed.

The decision is yours to make.

An ongoing discourse.

Preventing errors from occurring is always the best course of action, but when that is not a possibility, ensure it is human, helpful, humorous and humble.

Update (23/05/2014): Interestingly enough, I wrote this article (and published it privately) before eBay suffered a data breach recently. Impeccable timing.

Update (30/07/2014): There is a Tumblr dedicated towards shaming websites storing passwords in plaintext. Unlike the password hall of shame linked earlier in this article, PlainTextOffenders.com is new and kept more up-to-date with submissions from the community. I strongly recommend reading the Developers FAQ even though some of the points has already been highlighted in this article (albeit, not as succinctly).

Update (14/08/2014): Jeff Atwood from Coding Horror (and the co-founder of Stack Overflow / Stack Exchange) wrote a post in 2007 targeted towards developers "storing passwords incorrectly". It is worth a read albeit being dated.

Update (04/11/2014): Is it time for Passwordless Authentication? Researchers at Mozilla proposed an innovative approach towards login systems which relies on authentication tokens sent to the users' e-mail address or through SMS. Thoughts?

Update (30/01/2015): Duncan of Vents that Look Like Faces discussed the prospects of piggybacking on existing SSH technology and using it as an option for web sign-in. A demo was also developed as a proof-of-concept and assessments were made based on usability, deployability and security considerations (part of a scoring framework advanced in The Quest to Replace Passwords by Joseph Bonneau, Cormac Herley, Paul C. van Oorschot and Frank Stajano). These considerations allows us to consider the intricacies of attempts at replacing the conventional password system, and it allows us to contextualise the longevity as well as the prevalence of such system design. Through this framework we can weigh the relative advantages and disadvantages of alternative modes of login.

Update (11/09/2015): Anthony, the editor-in-chief of UX Movement, provides a case for removing the password confirmation field, and forced password masking as it is likely to lower conversion rate. Similarly, he recommends that a "show password toggle" should instead be offered.

By giving users control over their password input, you give them the peace of mind to complete your form.

Update (08/10/2015): Password Requirements Shaming is yet another Tumblr dedicated towards shaming websites with ridiculous password requirements / questionable management practices. Commentary is included for most of the offending sites.

Update (21/11/2015): In Patronizing Passwords, Joel writes:

We have to remember that at the end of the day, users are more than just a weak point of security in our systems. Our services exist for our users, not despite them. I like to think there are ways to get people to use strong passwords without forcing their hands and negatively affecting their experience using our products.

Update (01/12/2015): In The Password Paradox, the author mirrors the aforementioned arguments about password masking:

Clear text passwords do increase usability, but don’t force the change on existing users. Password masking is best offered as an option to maintain user trust in the site.